ASTMH Annual Meeting 2025

blogNew Round of Locally Acquired Malaria in the U.S.: Outlier or Warning Sign?

By: Matthew Davis, Burness

While involving a relatively small number of cases and not likely to be a harbinger of a major outbreak, a surprising spate of locally acquired malaria cases in the United States this year — the most widespread in 20 years — is raising questions about the domestic trajectory of the diseases.

Over the last few decades “in no single year did we ever see more than two different states with locally acquired malaria,” said Peter McElroy, Chief of the Malaria Branch in the Division of Parasitic Diseases at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

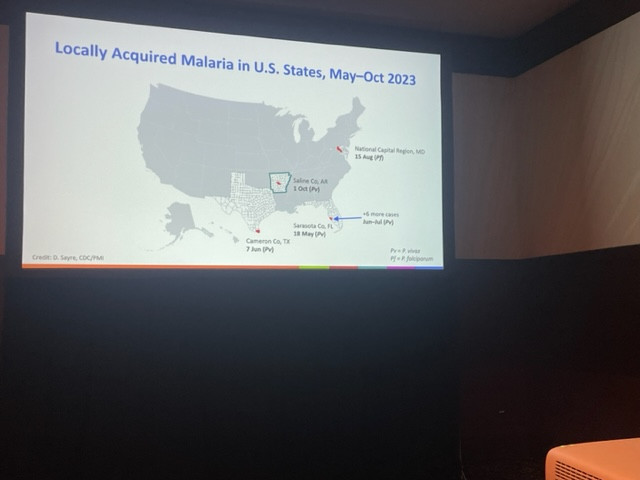

McElroy led a special session Thursday at #TropMed2023 to explore the details behind the 10 cases reported from four states — seven in Florida and one case each in Texas, Maryland and (just two weeks ago) Arkansas. All involved people with no history of recent international travel. While it is unusual to see locally acquired cases in so many states, McElroy said there have been periodic reports of local transmission since 1951, when the disease was considered eliminated in the U.S. Local infections are believed to occur when someone infected in a malaria-endemic region comes into the country and transmits parasites to domestic mosquitoes.

McElroy said that mosquito species capable of carrying malaria are found across large regions of the U.S. But he and his colleagues at CDC and state health departments that reported the recent cases said it’s difficult to determine whether this year is a quirky outlier or an indication that locally acquired infections will become more common.

“I think we can say that globally there’s more malaria around the world right now,” said Audrey Lenhart, head of the CDC’s Entomology Branch. “With so much travel, that means there is probably going to be more malaria within our borders (from travelers) and a greater likelihood that one of those people will come into contact with a local mosquito that is capable of transmitting it.”

All of the recently reported cases involved the plasmodium vivax parasite, except for the one infection in Maryland that was with the plasmodium falciparum parasite. Vivax malaria generally causes less severe disease. However, unlike falciparum malaria, if it’s not properly treated, vivax malaria can relapse months after the primary infection.

Andrea Morrison with the Florida Department of Health said almost all of the infections detected in her state involved unhoused people and were clustered in Sarasota County, which is on the coast in southwest Florida. She said the first case involved a 64-year-old man who sought out medical treatment after a two-week history of nausea and vomiting.

After ruling out other causes, physicians suspected the man may have been infected with babesiosis, a tick-borne parasitic disease that can produce symptoms and laboratory findings that are similar to malaria — and babesiosis is far more common in the U.S. She said physicians eventually consulted with CDC and later confirmed malaria via both rapid tests and PCR.

Morrison said this patient and the other six cases all were treated with anti-malaria medications and recovered. Subsequent efforts to trap and test mosquitos in the area found three that were positive for vivax DNA. But they were not carrying active parasites.

CDC’s Lenhart said tests of mosquitos captured near the Maryland, Texas and Arkansas cases all have been negative for malaria. Meanwhile, blood tests from patients indicated the vivax infections likely involved parasites that are genetically related to vivax parasites seen in Central and South America. The lone falciparum infection appeared to be related to malaria parasites found in central Africa.

In addition to being the only falciparum infection, the Maryland case also occurred much farther north than the other infections. Monique Duwell, who is chief of the state’s Center for Infectious Disease Surveillance and Rapid Response, said that while the state documents about 200 cases of travel-related infections every year, this was the first locally acquired case in more than 40 years. There have been no additional cases.

Morrison with the Florida Department of Health said it’s clear that homeless populations in Florida are more vulnerable for the simple fact that they spend more time out of doors. Several of the panelists at the session noted that simply living in a house with screens and air conditioning greatly reduces risks of being infected with a mosquito-borne disease. Morrison noted that these barriers are the likely reason locally acquired infections with dengue, another mosquito-borne disease, happen sporadically in Florida yet remain relatively uncommon. It was also the reason many panelists were skeptical that the U.S. could soon experience large-scale malaria outbreaks.

But the discussions at the symposium inevitably turned to questions of whether climate change is intensifying domestic malaria risks. The CDC’s McElroy said it’s a legitimate concern, especially with the last year being the hottest on record globally and many areas in the U.S. experiencing prolonged heat waves.

“We know that warmer temperatures speed up the parasite incubation period in the mosquito,” he said. “Is that’s what’s happening in the United States? We don’t know, but it is something we really have to keep our eye on after 20 years of no local (malaria transmission) events.”

Related Posts

By: Matthew Davis, Burness