ASTMH Annual Meeting 2025

blogScientists Can Tell Great Stories, Too - An Insightful First StorySlam at TropMed

By: Misia Lerska, Burness

Dr. Kristina Krohn is an internal medicine & pediatric hospitalist and an Assistant Professor at the University of Minnesota. What you might not know, however, is that she is also an excellent creative writing teacher.

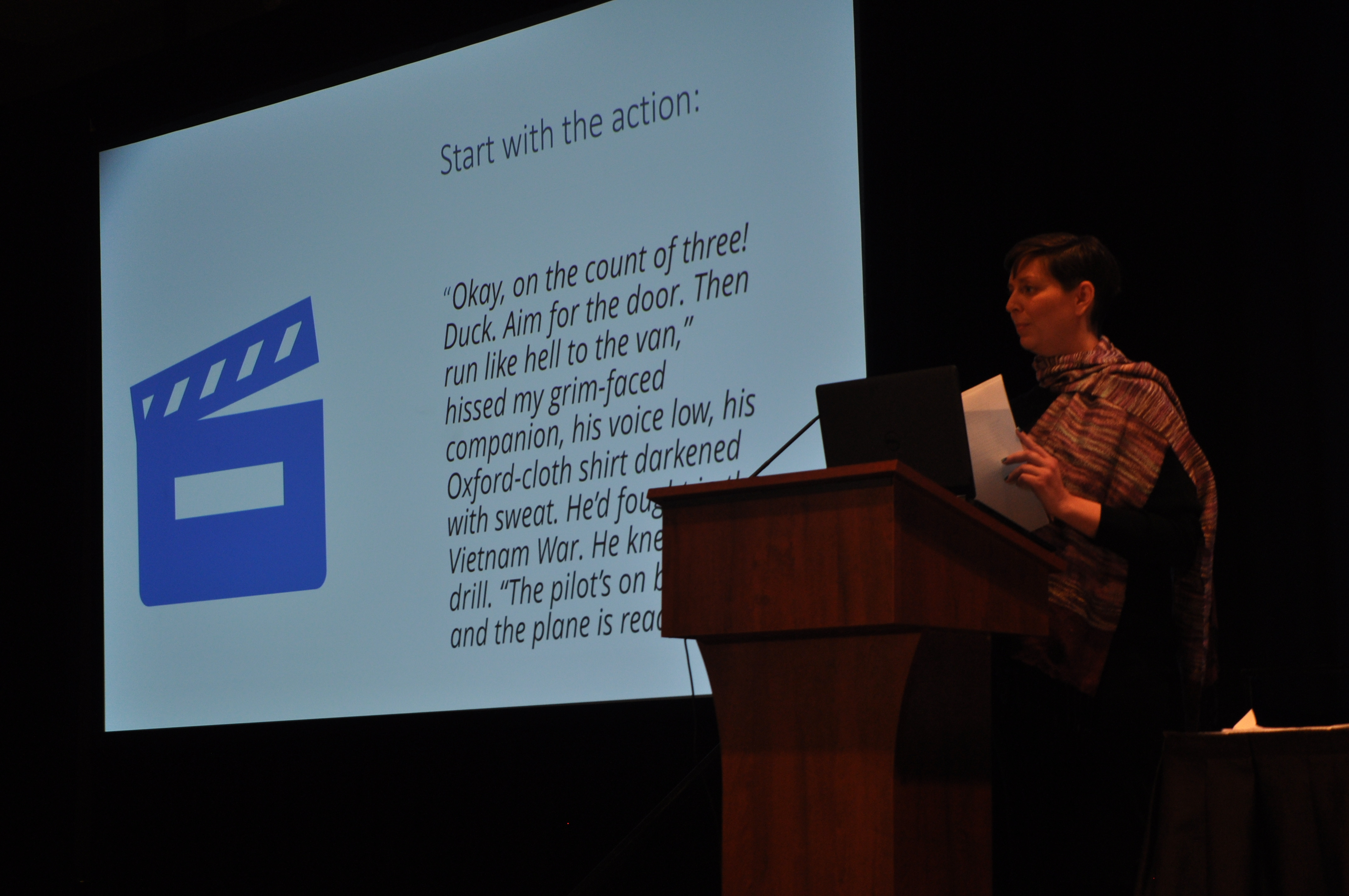

During TropMed22’s first StorySlam, Dr. Krohn explained what she looks for when reviewing story submissions, she poses the question: how can a scientist tell a good story? Usually, in STEM, you tell your audience the precise result and crux of what you’re trying to convey. She reminds us, however, of what our high school English teachers always berated us with: in storytelling, you show and don’t tell.

What follows, the amalgamation of various stories from the field in Tropical Medicine and beyond, reveals a very specific truth: Scientists can be great storytellers, too. Below are highlights from the ASTMH’s first StorySlam hosted by ASMTH’s Stories from the Field.

Dr. Peter Kilmarx – The Text Message

In August of 2007, Dr. Peter Kilmarx received a text message at 2:30AM from his friend, a traditional chief of a small village in the Democratic Republic of Congo. It read: “There's a lot of death from Ebola. When are you coming to build a hospital?”

Peter had been a Peace Corps volunteer in that small village in the 1980s, introducing tilapia fish farming in an attempt to counter protein malnutrition. Riding on his motorcycle with the wind flying in his ears, he grew close to the locals, many of whom named their newborn sons “Pierre” after him. At the end of his tenure, he remained close with the chief of the village, exchanging letters frequently.

It was now years later and Peter had finished medical school, beginning an entirely new life on the other side of the world. Despite not being able to understand how a village chief could recognize an outbreak, he sent a request for lab testing of 15 samples of sick people from the area. The tests confirmed what the chief already knew: Six out of 15 samples were positive for Ebola.

Dr. Kilmarx was returning to the area for the first time in 20 years and helped his friend manage the Ebola outbreak. He ran into a fisherman friend, who showed him an image of a 22 year old Pierre about to graduate from university. Everything had changed, but Peter felt a nostalgia for his Peace Corps days, reminding him of the passion he had found for life there.

When he asked the chief how he could have known it was Ebola, the chief answered that Peter had written him a letter describing what Ebola looked like—through friendship, Peter had given him the tools to diagnose and eventually heal his community.

Dr. Damasi Flavian Bayo – All Eyes On Me

On a day just like any other, Dr. Damasi Flavian Bayo was working in a hospital in Tanzania, and he received a call from the pediatric department to address a horrifying situation. A young boy had severe headaches and was vomiting constantly. As a child who had only lived 10 years, time felt longer to him: his illness felt like an eternity.

As he proceeded to examine the case, Damasi began to recognize an illness that he knew all too well: a severe case of meningitis. For the first time in his life, it felt as though all his years of education had culminated into the pain of one little boy. Memorizing his medical school education had been valuable—but it was only in that moment that he noticed a real problem with medicine in his country. There were just not enough MRI and CT scans available to truly help people. Even if establishments had the machines, many could not afford to use them. The reality was a lot of people are dying in Tanzania because they could not afford to live.

In this specific case, while explaining the treatment alternatives to the child’s family, he could see the pain in the boy's parents' eyes: his father could not earn a living while tending to his son, and his mother couldn’t tend to her other children while she was in the hospital. Damasi’s heart went out to them—so he discharged the boy early.

When he overheard that the little boy was still suffering from headaches, Dr. Bayo felt like he was going to explode. But he needed to respect the parents’ priorities and decisions. Luckily, thanks to antibiotics, the child recovered completely. What Dr. Bayo learned, however, is that a physician is not just for memorizing a book and enforcing its rules. There needs to be a balance between traditional allopathic methods and respecting local traditions.

Dr. Njeri Wamae – A Hygiene Class and Five Decades On

Dr. Wamae speaks with a cadence that sounds like footsteps.

She opened her session by showing a picture of her family from 1959; she is only three years old. Her family is sitting erect, proud to be together on a Christmas day. Njeri recalls her mother feeding her eggs because of their high nutritional value. The funny thing though, is that she always hated eggs. She would bury them in the backyard when no one was looking. Instead, she would eat the dirt. The dirt, you might ask? Yes, you did read that right. It is actually a symptom in those with a parasitic worm that consumes a person’s iron reserves. The iron helps to rebalance the blood. Luckily, Young Njeri recovered entirely.

This is a beautiful story to reflect on—especially given the fact that Dr. Wamae ended up specializing in parasitic worm infections and their implications on medicine at large. Now, she is able to heal communities while channeling the gut health of her childhood self from that first family portrait.

A Hidden Reality for Women in Science – Dr. Shaymaa Abdalal

What does a female scientist do in Saudi Arabia? That’s the question that Dr. Shaymaa Abdalal asked us while telling her story. She is Saudi, a mother and a practicing physician and researcher. But she didn’t follow the rules that were expected of her. Her community was shocked to hear that she was going to have her first child while attending medical school in the United States.

While in a foreign country studying a grueling degree, Dr. Abdalal had to bring her newborn daughter with their nanny to the ER while she passed her medical exams. Nothing in her life felt flexible. COVID-19 was the first time that she felt that people saw the importance of offering others the option to choose their schedules and create more balance. Now, she lives a better life, even though things can still be difficult. The key, she says, is to embrace the difficulty; this is how you create the future.

The Global Is The Personal – Dr. Nasreen Quadri

Dr. Nasreen Quadri grew up in the United States. Etched in her childhood memories, however, are her summers visiting her relatives in India. Her family’s relationship with food and the care they had towards her tender American stomach was the ultimate love language. Her mother would even boil bottled water “just in case.”

Despite the fear of getting sick, young Nasreen could never resist the beautiful fried peppers that she would eat on the street. Food could come in different shapes and cultural sizes, like the ice cream that she loved so much - that shift from the round shape of the American scoop to the Indian square. In a way, Nasreen was shapeshifting as well.

While leaving her family after those summer visits during her childhood, tears would stream down their cheeks as a way to shower each other with healing and love. That exact feeling is what outweighs the risk of traveling.

It’s unsurprising, of course, that Dr. Quadri now works in travel clinics, bringing her love of cultural exchange to her patients and beyond.

Part I: As The Worm Turns – Dr. Paul Pottinger

In the depths of the Delta surge, Dr. Paul Pottinger’s hospital in Seattle was literally underwater, having experienced extreme flooding and a plumbing disaster. Combined with the communal panic and trauma surrounding COVID-19 for physicians, Paul’s hospital and life were in a literal and figurative “shitstorm.”

That’s what made a text from his friend asking for medical advice all the more intriguing and exhausting. At the time, Dr. Pottinger had stopped sleeping in the same room as his wife to spare her the constant flooding of text messages throughout the night. This specific request mentioned a woman who went to Hawaii and quickly thereafter developed a severe rash that turned into tingling sensations and culminated in severe neurological symptoms, including double vision and perpetual exhaustion. It was nothing like he had ever heard before.

After meeting with the patient, Julie, Dr. Pottinger could not help but transpose his own feelings onto her; her condition was getting worse and this could have happened to literally anyone. After considering a brain tumor, multiple sclerosis and shingles, he finally found the answer: she had a rare form of rat lungworm eating at her brain. This was because of a salad that she ate while on the Big Island. The salad’s leaves had included a stowaway tiny slug carrying the rat lungworm parasite.

Dr. Pottinger’s diagnosis ultimately saved Julie, as he was able, in collaboration with other doctors, to fight the parasite. Dr. Pottinger would stay up late at night, unable to shake her case from his head. With time, faith and hard work, she did get better.

But this is not the story of a great worm, it’s the story of a great case. Doctors treat many patients in their lives, but it’s rare that they find a case that sticks with them. Through perseverance, care and love, Dr. Pottinger helped this patient get better. As he says, however, she was really the bigger teacher.

Part II: Trouble In Paradise – Julie Packard

It’s now been 10 months since Julie started feeling ill. She walks every day and recently completed a 16-mile hike.

Cut to her nine months ago, not being able to recognize herself in the mirror because of the puffiness in her face, weeping because she didn’t believe that she would ever get better. She had no idea that Dr. Pottinger was so worried about her, as she feels like a big reason that she was able to survive the illness was thanks to his constant reassurance. She understands that she is one of the lucky ones—not just because they found her diagnosis—but because she had access to excellent healthcare, which cannot be said for many others.

Looking back at what happened, she still feels like she would return to Hawaii because she now knows exactly what not to do. The problem, however, is that not many people who go there have access to the same information. There are specific steps that one could take, like signs in the produce section at the grocery store or at the baggage claim at the airport, that could save people’s lives.

It took her four interminable weeks to get diagnosed, but it shouldn’t have. Why not inform people, especially doctors to recognize this parasite? By sharing her story, Julie hopes it will become part of an ongoing process.

Related Posts

By: Matthew Davis, Burness