ASTMH Annual Meeting 2025

blogTropical Medicine’s Racist, Colonial Past—and How it Still Percolates in the Present

By: Matthew Davis, Burness

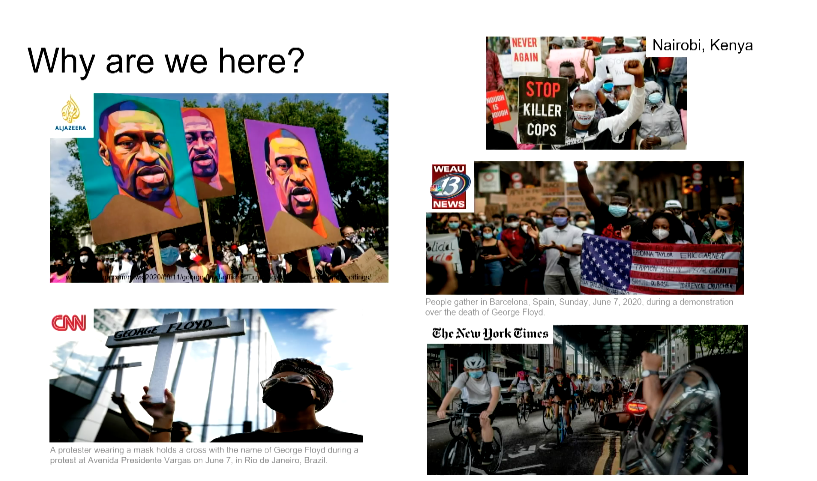

The racism and colonialism that was more overt in tropical medicine’s past produced power structures, hierarchies and attitudes that persist today—even in a field broadly infused with a genuine commitment to social justice through health equity.

That was one of the themes explored Thursday at #TropMed20 in a probing discussion of race and colonialism in tropical medicine. It was led by a panel of experts who drew on their compelling personal experiences and considerable professional skills to unpack how ASTMH and the broader field of global health should be guided by a past that many believe is still very much present.

“This is a Society of people of good heart who care,” said Linnie Golightly, MD, an expert in mosquito-borne and microbial pathogens, and Associate Dean of Diversity at Weill Cornell Medical College. “You go out to try to help and do good in the world. But what don’t we talk about?”

For example, Golightly pointed to the fact that the Society has had only three presidents who were not American-born and only eight of whom were women. And while it has many members from outside of the United States, she said they are “not necessarily in power.”

Golightly said she raised these points to encourage broader consideration of whether there remain vestiges of a Society founded in the early 20th century, a time when tropical medicine was deeply enmeshed with colonialism, that still influence its power dynamics.

“I think we are a Society that can look each other in the eye and face the hard things and work together to move forward,” she said.

Thomas LaVeist, PhD, Dean of the Tulane School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine, said that percolating through the day’s discussion about whether the troubled history of tropical medicine was still playing out in the present day was the issue of “narratives—who controls the narrative, who writes the narrative, and which narrative becomes dominant.”

He recalled a recent interview with a reporter who asked whether memories of the Tuskegee experiments, in which hundreds of Black men in Alabama were intentionally denied treatment for syphilis, would prompt Black communities today to be skeptical of COVID-19 vaccinations. LaVeist said that, interestingly, surveys of Black and White Americans have shown that neither group knows much, if anything, about the Tuskegee experiments. However, when given the details of Tuskegee and then asked whether something similar could happen today, he said most White respondents said “of course not” while Black respondents “almost uniformly said ‘of course this could happen.’”

The issue is relevant, he said, because it’s an example of a dominant narrative that assumes racial injustice is largely a thing of the past—and that something like mistrust of medical research in minority communities is solely about historical memories.

“This is important because it’s not some historical event that leads to the mistrust,” he said.

Rather, LaVeist said, it’s more the everyday experience of Black people, who regularly encounter racism from individuals and institutions, that makes such mistrust “logical and rational.”

Jonathan Stiles, PhD, Professor of Microbiology at Morehouse School of Medicine and an ASTMH Board member, said one perplexing problem is, given the large number of global health programs and projects located overseas, how funding agencies and recipients manage the power relationships while maintaining a commitment to equity and inclusion.

“In many instances, we find these power relationships tend to create more problems when it comes to inclusion,” he said.

Mishal Kahn, PhD, a social epidemiologist with the Decolonizing Global Health initiative at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, raised a provocative alternative to the conventional view that global health research institutions and organizations are all about increasing equity and social justice.

“That is one definition,” she said. “But another definition I read recently is that global health is actually a brand used to describe the work of high-income countries extracting information, knowledge and power from low-income countries.”

Kahn said that as the global health community reflects on its commitment to inclusion and diversity, it’s worth asking whether people who benefit from the current system--in which the most influential institutions are controlled by wealthy countries—are willing to be involved in dismantling it.

Incoming ASTMH President Julie Jacobson, MD, DTMH, Managing Partner of the global health NGO Bridges To Development, said the panel was engaging in “one of the most important issues of our time.” She said there has been considerable interest within the Society in a frank and open dialogue on the colonial roots of tropical medicine as part of its ongoing focus on fostering diversity, which has included developing a strong Inclusion and Respect policy.

“The majority of members felt this was an important issue for us to discuss openly and think about how it reflects on how we work together in the future,” she said.

More Information: https://www.abstractsonline.com/pp8/#!/9181/session/332

Related Posts

By: Matthew Davis, Burness