ASTMH Annual Meeting 2025

blogQ & A with Incoming ASTMH President Joel Breman

By: Matthew Davis, Burness

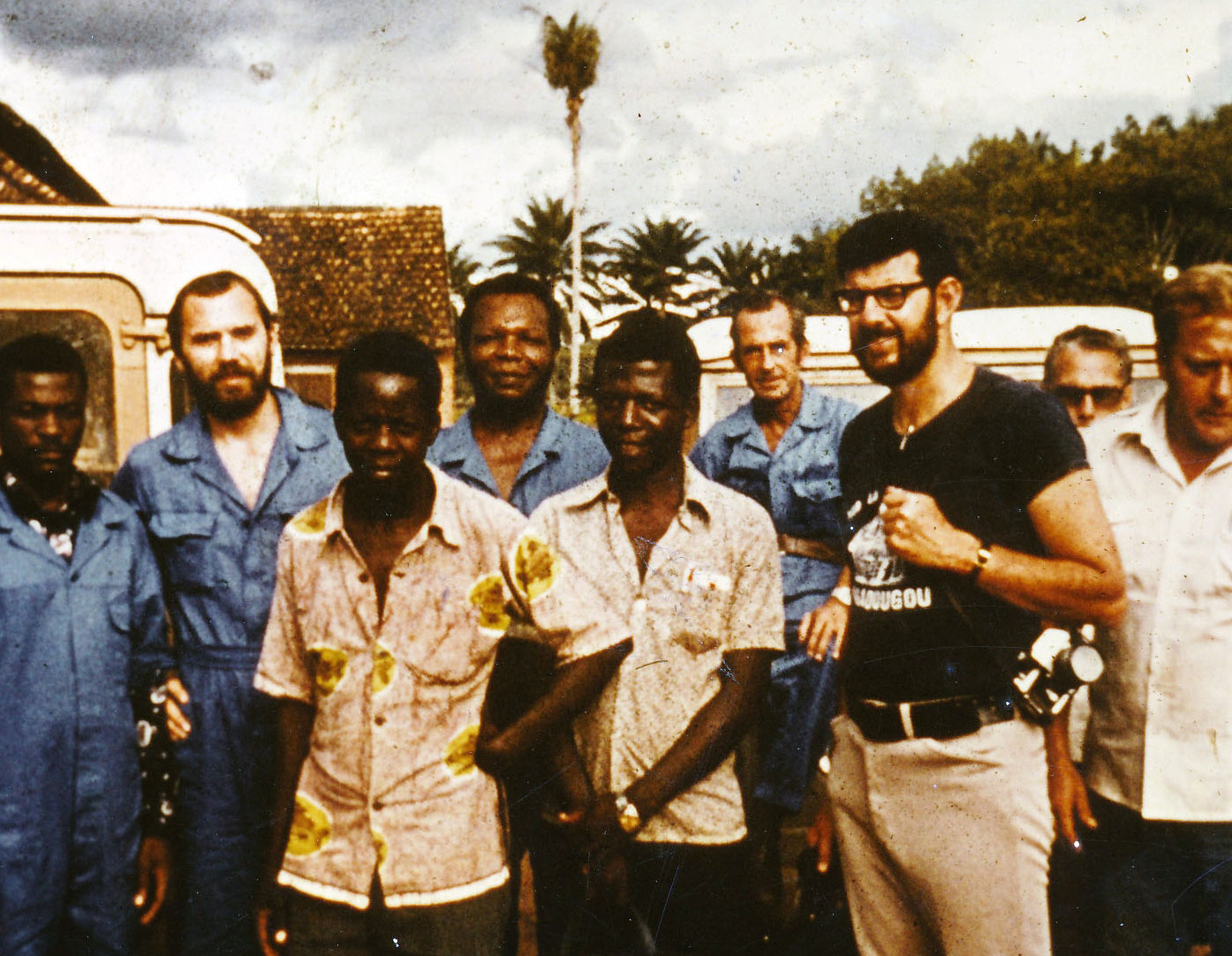

Joel Breman, MD, DTPH, FASTMH, Scientist Emeritus with the Fogarty International Center at NIH, recently assumed the role of ASTMH President. Breman is internationally known for his work on Ebola, smallpox, malaria and other diseases. He was part of the team that in 1976 investigated the first known outbreak of Ebola Virus Disease and also served as Deputy Chief of the WHOs Smallpox Eradication unit. He recently sat down with science writer Matthew Davis to discuss his plans as President and thoughts on a number of other related issues.

You’ve had such a distinguished career in biomedical research and global health. What attracts you at this point in your career to assuming the role of President of the society?

I am healthy and I want to contribute, with the benefit of past experience and a modern perspective. I have participated in virtually all annual meetings since 1981 and I feel like I have some ideas to help make the Society more relevant to the current times. I also am very aware of the current epidemiological and demographic shift in a number of conditions and diseases.

Among other things, I was closely involved as an editor for the second edition of Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. And I have a long-standing interest in how we can contribute to understanding and controlling epidemics. More recently, I have become very aware, especially from our young members, about the connection between the burden of disease and overall planetary health. I would like to see the Society expand its focus in this area.

What are your priorities for the coming year? What would you like to accomplish?

One of my priorities is to consider different ways of educating members of Congress to give them a greater appreciation for their role in addressing global health concerns. There’s a fair amount of turn-over in Congress every two years and that requires a constant focus on education. I think the Society has been doing a great job overall. The awareness of global health challenges among members of Congress is much higher than when I began in this game over 50 years ago.

What I have proposed is that we go beyond seeking out members when they are in Washington and look for ways to engage them in their home districts. You can generally find something in every state that can help draw attention to the issues we care about—an infectious disease threat, research supported by NIH, CDC, the National Science Foundation or even the Department of Defense that is being carried out by a local institution.

If we emphasize these connections through local media or in meetings in their district with scientists who also are their constituents, that’s more likely to capture their attention and support. The recent Eastern Equine Encephalitis outbreak, the measles outbreaks globally (and vaccine refusal), refugee and immigrant health problems, and the exciting research on new drugs, vaccines and delivery approaches for malaria and NTDs come to mind.

A veteran disease fighter: Dr. Joel Breman, pictured at far right, in 1976 with an international team in the Democratic Republic of Congo responding to a disease later identified as Ebola. (Credit: Dr. Joel Breman)

As someone closely connected to the evolution of U.S. support for biomedical research, how do you view the current landscape, in terms of overall funding and also support within NIH institutes and centers for research that has a more international focus?

There continues to be strong bipartisan support for NIH funding overall. And while the Fogarty International Center at NIH is the only one with international in its name, I think there has been significant progress across all of the 27 institutes and centers in understanding the benefits that emerge from assuming a more international focus. You saw it first with HIV research and the importance of collaborations with African scientists. But you can also look at many other institutes, in places like Heart, Lung and Blood; Child Health; and in work related to trauma/surgery, genetics and mental health—and see an increasing focus on global partnerships, a lot of it coordinated through Fogarty. So, I think a great majority of the institutes are interested in global health and I believe there are many opportunities to expand those collaborations.

How can the Society support efforts to develop more international research collaborations?

It is increasingly critical that we support efforts to build capacity and leadership in the countries that are suffering the greatest burden of disease. You can look at several areas of the world today and see countries moving fast to develop a host of new capabilities. But there is still a need for more resources, technology and training.

I think the Society can contribute by expanding our presence and raising our profile globally. That can include support for tropical medicine societies abroad and providing more awards for scholars to present at our Annual Meeting.

The Society has made statements recently regarding influenza vaccinations for migrants at the border and also regarding the response to the Ebola outbreak in the DRC. How should the Society be using its voice to draw attention to and improve public understanding of key global health concerns?

One thing on the top of my lists is to form an Epidemic Response Group—not a group that would send commandos to the front lines but rather a group that can rapidly develop analytics and options for confronting an outbreak. The Response Group could also move quickly on communications—writing op-eds and using social media to complement the tactical advice. That way, when there is something like the recent Ebola outbreak in DRC, the cholera outbreak in Yemen, the massive increase in malaria in Venezuela or a situation with refugee health, we can move more quickly to mount a coordinated response. We can assemble a group of experts and make them available to offer their expertise—to governments and the media. Because if there is one thing we are not lacking as a Society it is expertise.

Plus, a quarter of our 4000 members reside in low- and middle-income countries. They are close to—often involved in—the action directly. They can keep us informed and represent the Society locally when emergencies occur.

The rise of anti-science sentiment, from climate change denial to a growing coalition of anti-vaccination activists, has generated a certain amount of pessimism about public support for science. Looking at things from a more hopeful angle: What gives you hope for progress in global health research?

In 2020 the world will be marking the 40th anniversary since the eradication of smallpox, one of the greatest triumphs of the modern world. And we need to really speak out about the many things that have succeeded—including major reductions in guinea worm and onchocerciasis, and significant reductions in the burden of diseases like polio, diphtheria, tetanus and measles due to the widespread availability of vaccines. And we have to publicize recent breakthroughs, like one pill for HIV, all of the new treatments for tropical diseases and the dramatic reductions in deaths from malaria.

More people need to see how embracing and investing in this type of scientific research produces incredible progress—and that new advances are paving the way for even greater breakthroughs. So, despite the challenges and setbacks, I think we need to keep focused on the very positive results that science brings to society. And in global health, when I look at the exciting work underway today in many different areas, I feel like the good old days are yet to come.

Related Posts

By: Matthew Davis, Burness