ASTMH Annual Meeting 2025

blogOf mice, men and malaria

By: Rebecca E.k. Mandt, Ba, Harvard T.h. Chan School of Public Health

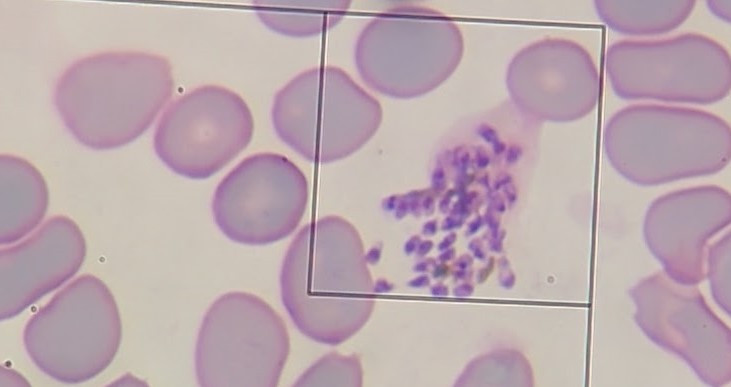

The life of a malaria parasite is complicated. As a vector-borne disease, these parasites must be able to survive both in the human host, and in the mosquito that carries them. Inside the human host, the parasite goes first to the liver, and then spends most of its time replicating in the bloodstream. Untangling which genes are important for each of these lifecycle stages is challenging. As anyone studying the biology of malaria can attest, there are a lot of unknowns. In fact, almost half of the parasite’s genes are unannotated, meaning we do not know their function.

Thursday morning’s TropMed19 session entitled “Large-Scale Genome-Wide Approaches to Identify and Study Potential Antimalaria Drug Targets and Resistance Factors” was started off by Dr. Ellen Bushell of the Laboratory for Molecular Infection Medicine in Sweden. She, along with collaborators, worked on the PlasmoGem project, which aimed to do a genome-wide screen, using an innovative genetic editing technique to efficiently disable, or “knock out” individual genes in Plasmodium berghei—a malaria parasite that infects mice. Dr. Bushell then characterized the growth of these knockout parasites. Because each of the parasites carries a unique genetic “bar-code”, she was able to distinguish which ones could survive in the mouse, and which ones could not, and match that back to the specific genes that had been disrupted. She reported the results of this study in a landmark manuscript published in Cell in 2017. As a malariologist myself, I can attest that everyone rushed to check whether their own favorite gene of interest was identified as essential for parasite growth in the study.

However, the unique advantage of using this mouse model of malaria is that we can look at more than just the blood stage of the parasite. In her talk, Dr. Bushell spoke about new work using the same pool of knockout parasites to identify genes that are involved in the parasite’s decision to become a gametocyte—the sexual stage that is able to be picked up and transmitted by mosquitoes. She also worked with her collaborators in Volker Heussler’s lab at the University of Bern, who can experimentally infect mosquitoes and have them feed on the mice, thus allowing them to study the full life cycle of the parasite. From this work, they were also able to identify genes important for parasite survival and growth in liver cells. Ultimately, this work makes big strides towards understanding the complex life cycle of the malaria parasite—knowledge that will be critical to identify new drug targets.

Other session speakers reported on other innovative work using genome-scale approaches to identify genes involved in parasite growth and survival, as well as genes involved in drug resistance. Overall, it was an exciting session that left the audience dreaming big.

Rebecca is a 5th year graduate student in the laboratory of Dr. Dyann Wirth. TropMed is one of her favorite events of the year.

Related Posts

By: Matthew Davis, Burness